Something is seriously wrong with the experts setting policy today. They are dead set on endangering lives by pushing failed strategies.

Last week Dr. Manoj Jain, Captain of the COVID Task Force, scribbled an opinion in which he argues that “masking is the seat belt of today.”

There are just a few problems with this analogy.

First, the supposed benefit of masks is protecting the other guy, not yourself.

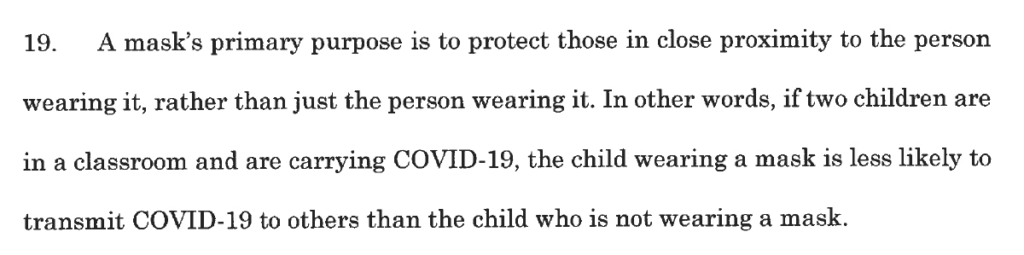

That’s what Shelby County argues in its legal complaint against Governor Bill Lee’s executive order, as stated in the excerpt below.

If Dr. Jain’s analogy is valid, you’d be protected in a collision by the truck driver’s seatbelt, not your own. (That, of course, is obviously nonsense.)

Second, if seatbelts were like masks, we’d all be looking for better seatbelts. Nobody with half a brain would take the supposed experts at their word and strap in with a paper seatbelt.

And if auto manufacturers produced vehicles with seatbelts of such poor quality, consumers would sue them into bankruptcy.

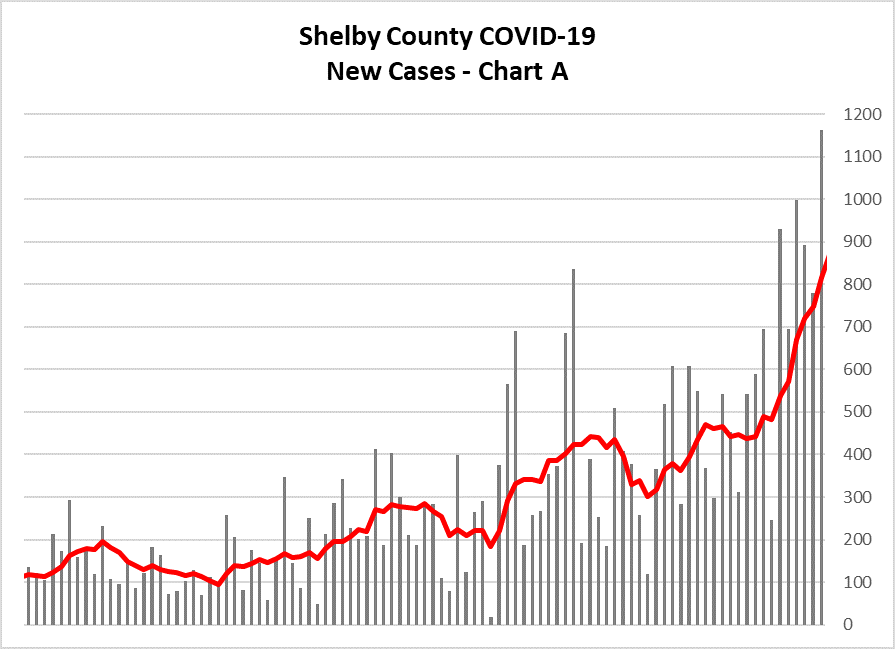

Anyone taking even the slightest glance at the crash test data would conclude that paper seatbelt mandates aren’t producing the desired results.

In addition to the search for a better seatbelt, we’d all be looking for additional protocols and technologies, such as airbags, anti-lock breaks, cameras and sensors, frame and windshield improvements, etc.

We wouldn’t sit around like a bunch of dummies listening to public health experts who refuse to learn anything from the thousands and thousands of lives lost despite overwhelming compliance with mask rules.

The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.

The mandates have not worked.

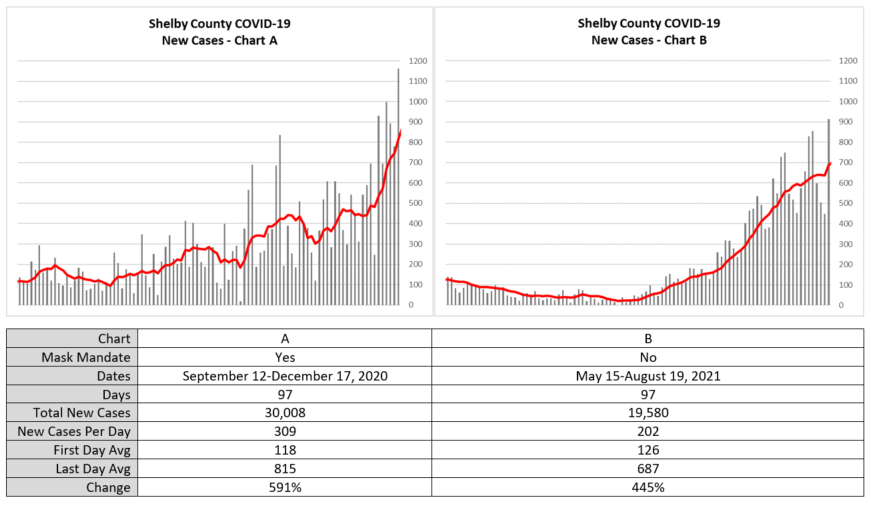

Here’s yet another illustration of that fact. Take a look at the two charts below. Which one represents a period with a mask mandate in place?

Both charts cover the same number of days, and they are both real case curves in Shelby County.

The answer key is below.

The period covered by a mask mandate had more total cases, a higher daily average, and a larger percentage increase in new cases.

Considering this data, isn’t it possible that:

- The mask mandate did not “flatten the curve.”

- Other factors play a bigger role in transmission.

- We could identify other mitigation strategies that might work better.

If any of these propositions are true, let’s end the political mask wars.